Is Mathematics the Language of the Universe? Decoding the Cosmic Blueprint

In 1960, the physicist and Nobel laureate Eugene Wigner published an essay that continues to haunt the scientific community. Titled “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences,” it posed a question that sits at the uncomfortable intersection of physics, philosophy, and evolutionary biology: Why does mathematics work so well?

We often take for granted that the scribbles on a chalkboard can predict the orbit of a planet or the stability of a bridge. But there is no logical necessity for this to be true. Why should the chaotic, messy, physical world adhere to the rigid, logical structures of human thought?

Fundamentally is mathematics the language of the universe—a code waiting to be discovered? Or is it merely a model we have invented, a grid we paint over reality to make sense of the chaos?

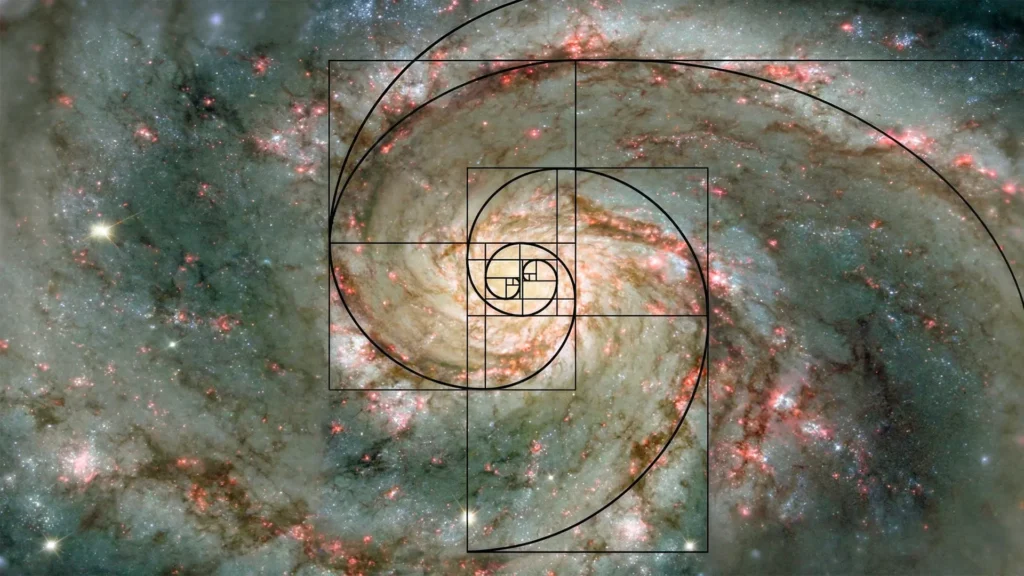

To answer this, we must look not at the abstractions of the mind, but at the concrete evidence in the world around us, from the spiraling geometry of a flower to the crushing gravity of a black hole.

Is Mathematics the Language of the Universe? Decoding the Cosmic Blueprint

The Biological Algorithm: Optimization, Not Aesthetics

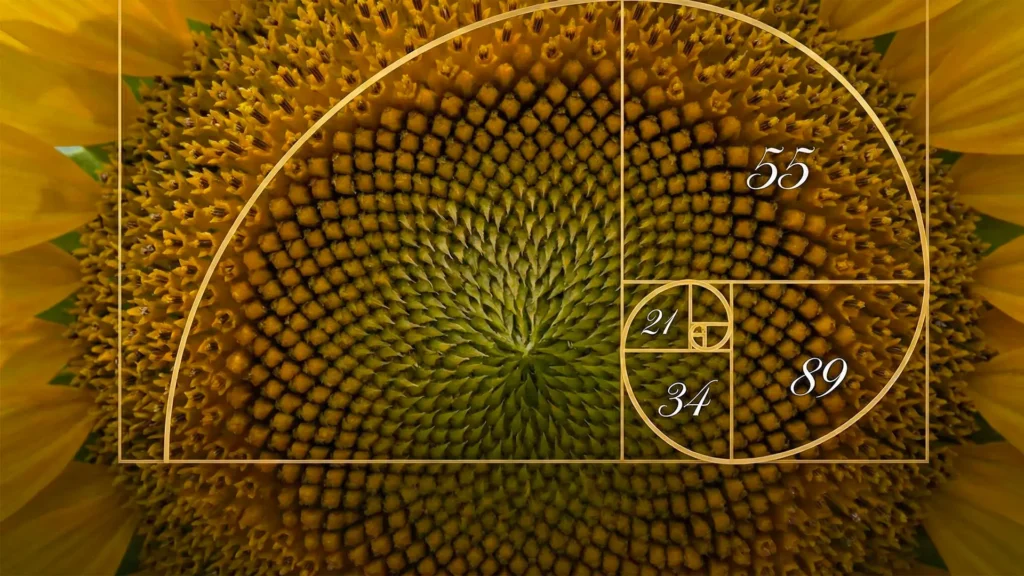

If you were to design a solar panel system for maximum efficiency, you would want to ensure that no panel casts a shadow on another. Nature, the original engineer, solved this optimization problem millions of years ago.

Consider the sunflower. If you look closely at the arrangement of seeds in its head, you will notice a distinct pattern of interconnecting spirals. Count them, and you will almost invariably find numbers that belong to the Fibonacci sequence: 21, 34, 55, 89.

The sequence is simple: start with 0 and 1, and each subsequent number is the sum of the previous two (0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13…). But its appearance in nature is not a quirk of aesthetics; it is a matter of survival.

In botany, this phenomenon is known as phyllotaxis. If a plant were to grow leaves or seeds at random angles, they would overlap, blocking sunlight and wasting space. If they grew at simple angles (like 90 or 180 degrees), they would form straight lines, leaving gaps.

Nature’s solution is to arrange growth at an angle related to the Golden Ratio (Φ≈ 1.618), which is deeply connected to the Fibonacci sequence. This specific angle ensures that each new leaf or seed pops up in the space least occupied by the previous ones. It is a mathematical solution to a physical resource problem.

This suggests that mathematics in biology is functional. It is an algorithm selected by evolution because it works. But this “functional” explanation hits a wall when we move from biology to physics. In biology, math is a tool for survival. In physics, it appears to be the blueprint of existence itself.

Is Mathematics the Language of the Universe? – The Predictive Lens: Seeing the Invisible

The strongest argument for mathematics as the “language of the universe” lies in its uncanny ability to predict phenomena long before they are observed.

In 1915, Albert Einstein published his theory of General Relativity. It was a masterpiece of mathematical geometry, describing gravity not as a force, but as the curvature of spacetime. While the equations were elegant, their implications were terrifying.

A few months later, Karl Schwarzschild, a physicist serving on the German front lines of WWI, found a specific solution to Einstein’s equations. He calculated that if a massive amount of matter were compressed into a small enough radius, spacetime would curve so violently that nothing—not even light—could escape.

At the time, this was purely a mathematical derivation. There was no observational evidence for such objects. Einstein himself regarded them as a mathematical curiosity, a “singularity” that likely didn’t exist in the real world.

He was wrong. The math was right.

Decades later, astronomers discovered Cygnus X-1, and eventually, the Event Horizon Telescope gave us the first image of a black hole in the center of galaxy M87. The universe was obeying a rulebook written in calculus. The black hole existed on paper almost a century before it was seen in the sky.

This pattern repeats throughout history. In 1928, physicist Paul Dirac was working with equations to describe electrons. His formula (x2 = 4) allowed for two solutions: a positive energy electron and a “negative” energy counterpart. Rather than discarding the mathematical anomaly, Dirac posited that “antimatter” must exist. Four years later, the positron was discovered.

When mathematics leads discovery, rather than just describing it, we are forced to consider the Platonist view: that mathematical forms are the primary reality, and the physical world is a shadow of these perfect truths.

The Anthropocentric Counter-Argument

However, we must temper this “scientific mysticism” with cognitive rigor. There is a compelling counter-argument rooted in neuroscience and evolutionary psychology.

Perhaps mathematics feels like the language of the universe because it is the only language our brains are capable of speaking.

Cognitive scientists Lakoff and Núñez, in their work Where Mathematics Comes From, argue that our mathematical concepts are grounded in our physical embodiment. We understand “sets” because we can hold objects in our hands. We understand “continuity” because we move through space.

If the universe were truly mathematical, why does the map sometimes fail the territory?

- Chaos Theory: Simple, deterministic equations can lead to wild, unpredictable behavior (the Butterfly Effect). We can calculate the motion of planets for millennia, yet we cannot predict the weather three weeks from now.

- Quantum Uncertainty: At the subatomic level, the rigid determinism of classical math breaks down into probabilities. We can no longer say “X is here”; we can only say “X is likely here.”

This friction suggests that while math is incredibly effective, it may be an approximation—a low-resolution rendering of a high-resolution reality. As the statistician George Box famously said, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

The Max Tegmark Hypothesis: The Mathematical Universe

Pushing the scientific temper to its extreme, cosmologist Max Tegmark proposes the “Mathematical Universe Hypothesis.” He argues that the universe doesn’t just have mathematical properties; it is a mathematical structure.

In this view, the “Theory of Everything” that physicists search for is not a set of equations describing the world. The equations are the world. We, the observers, are “self-aware substructures” within this vast mathematical object.

This radical idea solves the problem of Wigner’s “unreasonable effectiveness.” Math works perfectly to describe physics because physics is math. There is no separation.

Conclusion: The Silent Code

So, is mathematics the language of the universe?

The evidence suggests a nuanced reality. In the biological realm (the Fibonacci sequence), mathematics appears as an emergent property of efficiency—a convergent evolution of logic. In the cosmological realm (Black Holes), it appears as a fundamental law, a predictive structure that precedes observation.

As we continue to explore the cosmos—and as we build artificial intelligences that speak in vectors and matrices—we are essentially mining the bedrock of this reality. Whether we are discovering the code or inventing it may ultimately be a distinction without a difference.

For now, we can say this with certainty: The universe is not silent. It hums with a frequency we have learned to measure. And as we listen closer, the melody is undeniably, beautifully mathematical.

Is Mathematics the Language of the Universe? Decoding the Cosmic Blueprint